For a long time, ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate) and CRP (C-Reactive Protein) have been the primary biomarkers for assessing inflammation.

ESR indicates the overall inflammatory state, while CRP is produced by the liver in response to inflammation or infection.

However, these “acute-phase” proteins have limitations in specificity and sensitivity for identifying low-grade inflammation.

Other biomarkers related to specific immune pathways are more accurate for this type of inflammation.

BAFF and PAF

BAFF and PAF are new biomarkers of inflammation related to immune contact with food.

BAFF is a protein involved in inflammation, produced by various immune system cells (such as macrophages and T cells), as well as by adipose tissue and epithelial cells in the respiratory tract.

PAF actually represents a family of phospholipids that mediate physiological and pathological processes, including inflammation. PAF is secreted by a variety of immune system cells, such as platelets, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages, as well as by endothelial and smooth muscle cells.

The term “food intolerance” has been widely misunderstood and has often led to the dangerous elimination of foods from the diet, based on specific symptoms or on unscientific “food intolerance” tests.

Both markers can be used as “thermometers” to assess the extent of systemic inflammation, including that related to food. Their levels rise in response to external and internal stimuli, contributing to inflammatory conditions and autoimmune diseases. Although they are not exclusive markers of food reactions, they are influenced by diet and can be used to implement nutritional adjustments and evaluate the need for further diagnostic investigations.

Allergy, intolerance, and food-related inflammation: comparative concepts

In 2017, the New England Journal of Medicine confirmed the correlation between BAFF and the development or maintenance of autoimmune diseases, thus opening new possibilities for diagnosis and treatment.

The TNFSF13B gene was identified as responsible for the synthesis of BAFF, and a genetic variant, BAFF-var, has been associated with an increased risk of autoimmunity. However, this variant only accounts for a portion (24-27%) of cases of elevated BAFF levels, with the majority being attributed to environmental factors, including diet. The presence of BAFF-var is found in a variable percentage of the population, with a higher incidence in certain regions like Italy and Spain.

This predisposition should be managed by activating more suitable epigenetic mechanisms (lifestyle, diet, and personalized supplementation).

Food allergies, food intolerances, and food-related inflammation are distinct concepts that are often confused. The only food intolerances recognized by the scientific community are celiac disease and lactose intolerance, both of which are irreversible. Additionally, lactose intolerance is dose-dependent and does not involve the immune system.

The term “food intolerance” has been widely misinterpreted and has often led to the dangerous elimination of foods from the diet, based on specific symptoms or unscientific “food intolerance” tests. What often follows is the exclusion (even temporarily) of specific foods from the diet, which fosters aspects of malnutrition, dietary inadequacy (especially in young people), and can lead to strong immune-mediated reactions upon reintroducing those foods.

Role of IgE and IgG

Immunoglobulins E (IgE) are antibodies produced in response to contact with food and bind to receptors on the surface of mast cells. Mast cells are a type of white blood cell found in connective tissues and mucous membranes. When this happens, a series of events are triggered that lead to the release of inflammatory mediators such as histamine and TNF-alpha. These mediators cause an inflammatory response, usually manifesting within a few hours of consuming a particular food.

Immunoglobulins G (IgG) are also a type of antibody produced by the immune system in response to exposure to various antigens, such as food antigens, pathogens, and toxins, and play a key role in defending the body against infections, contributing, among other things, to our immune memory.

The interaction between IgG, IgE, and food antigens depends on the relative concentration of these three elements, and depending on the situation, can provoke different responses from the body. Specifically, when IgG antibodies are present in excess compared to antigen levels, they “intercept” the antigen and block its binding to IgE. However, the antigen-IgG complexes created in this way can bind to other immune cells and trigger an IgG-mediated response.

IgG antibodies against foods are typically produced by the body when it comes into contact with food, and their levels increase proportionally with repeated exposure to the same category of food.

According to the model described above, a high number of “encounters” between antigen-antibodies of IgG, due to the repeated intake of the same food stimulus, promotes low-grade inflammation by activating an immune response mediated by this class of antibodies.

Many studies have described a correlation between IgG and inflammatory conditions such as Crohn’s disease, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS). All of these studies have shown that an appropriate therapeutic intervention can improve symptoms, highlighting the clinical relevance of IgG in determining delayed reactions involving IgG, macrophages, PAF, and BAFF. This was also demonstrated in a scientific study conducted by our team, where adherence to a specific diet was correlated with a reduction in IgG levels.

The great food groups

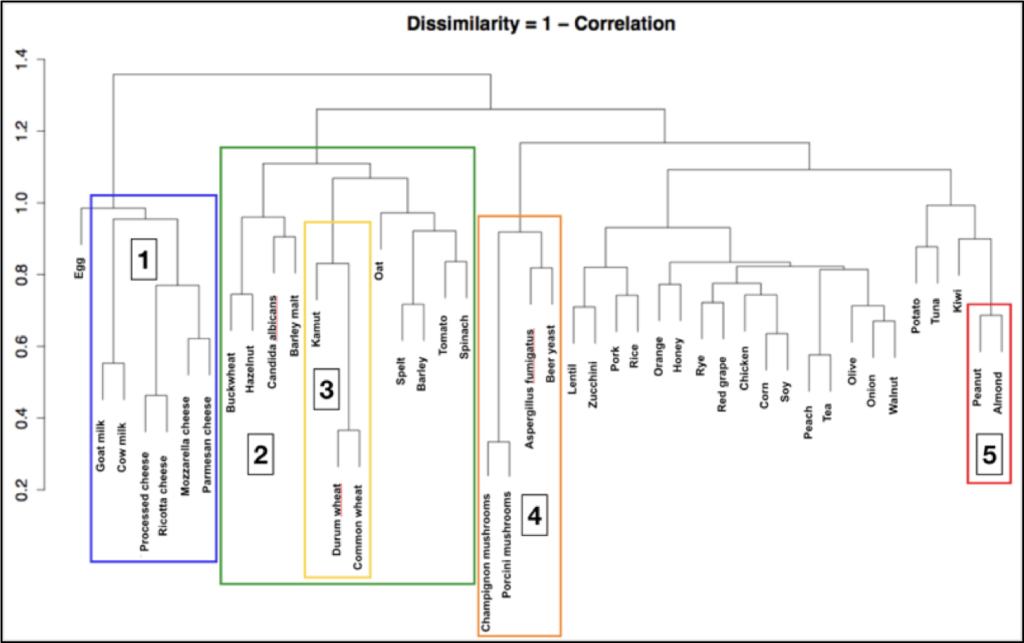

IgG antibodies are a class of antibodies with highly variable structure and form. Their low antigen affinity means that they do not recognize a single food antigen with extreme specificity but instead recognize common antigens found in one or more food classes that share similar protein structures.

This has been confirmed both by various studies on the structure and function of this specific class of antibodies and by statistical studies that have allowed researchers to examine the distribution of food-specific IgG immunoglobulins in the Italian-European population.

Based on this “immunological similarity,” foods are classified into five major groups:

Wheat and gluten: this group includes gluten-containing cereals such as wheat, Kamut, spelt, barley, rye, and all their derivatives. It also includes preparations containing gluten, such as soy sauce, beer, barley coffee, and so on.

Nickel: this group includes foods such as tomatoes, spinach, oats, mushrooms, cocoa, and foods preserved in cans, such as canned tuna, canned sardines, etc.

Yeasts and fermented products: this group includes vinegar, alcoholic beverages such as wine and beer, mushrooms, cheeses, baked goods with or without yeast, industrial citric acid (E330), soy sauce, yogurt, industrial mayonnaise, honey, etc.

Milk and beef: this group includes milk and dairy products (yogurt and cheese), as well as beef and beef derivatives, such as bresaola (lactose intolerance, which is a sugar-related enzymatic condition, has nothing to do with the inflammation associated with the milk group).

Cooked oils: all foods containing cooked vegetable oils, such as cookies, rusks, crackers, flatbreads, chips, roasted nuts, sautéed foods, and fried foods.

By the Scientific Editorial Team at GEK Lab